A sermon preached by the Reverend Sarah Grondin, at St. Jude’s Anglican Church, on Wednesday, November 12, 2025.

I speak to you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, Amen.

Have you ever had the experience of feeling uncomfortable with yourself, for whatever reason? Like you just can’t get comfortable in your own skin? You were all teenagers at some point, so I’m sure you have at least an inkling of what I mean.

Maybe this discomfort we experience is because we constantly compare ourselves and compete with each other. Maybe it’s because we feel like expectations are placed on us that we just can’t meet. Maybe we feel lonely and isolated from our family, our friends, or even here at church.

When we find ourselves in these kinds of situations, we wish we had a new-skin… one that was comfortable, one that fit better, one that allows us to feel accepted and approved by others. Our Gospel story from Luke today has something to say about living a skin-deep life and what it means to be not just comfortable, but whole.

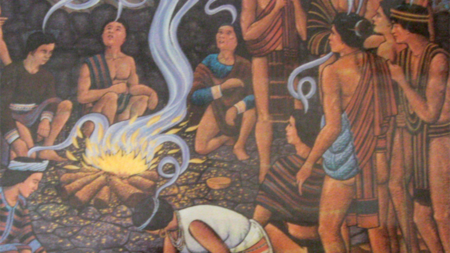

Luke begins by telling us that Jesus is on the way to Jerusalem—the place where he will ultimately give his life, the place of death and resurrection—and on the way he meets ten people who are themselves as good as dead. Ten lepers.

In the world of the Gospels, leprosy meant more than just a skin disease. It was a living death. People with leprosy were cut off from family, from community, from worship. They had to live on the edges of society, shouting “Unclean! Unclean!” whenever someone passed by, so no one would come too close. It was a desperate existence, and their skin was their sentence.

And into that living death walks Jesus. When the lepers see him they call out to him, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us!” The only other people in Luke’s Gospel to call Jesus “Master” are the disciples. The lepers are able to recognize Jesus on a level that others either can’t see or refuse to see. They know that Jesus can heal them, because they know the One who sent Him.

When the lepers call out to him, Jesus doesn’t flinch. He doesn’t step back or walk the other way. He simply tells them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” Which might seem like an odd thing to say… because what’s a priest go to do with leprosy?

But in Jesus’ day the priests had a strange double function of also serving as a health official, and in that role they had the responsibility and the power to examine those who were suspected of having any kind of disease that would make them unclean.

In the book of Leviticus, all of chapter 13 is devoted to the laws concerning leprosy and leprous garments. The law goes into very specific detail regarding what state the person is in and what their sores look like… which I’ll spare you from recounting. If you’ve got a strong stomach and you’re curious, you can read that later on your own.

But the thing I want you to take away from this is that the priest had the power to pronounce whether a person was clean or unclean, which in Jewish society could be the difference between life and death. In order to be accepted back into community, it wasn’t enough to no longer have the illness or disease, a priest had to determine that the person was now clean.

So Jesus tells them, “Go show yourselves to the priests.” And as they go, Luke tells us they were made clean. Skin made whole. Bodies restored. The surface healed.

The joy must have been overwhelming for them—they would finally be able to return to their community, and their families, to see their friends again, and to find work to support themselves. These ten lepers who had been healed, were now comfortable in their own skin again.

But then the story turns.

Only one of them—a Samaritan, who was an outsider among the outsiders—turns back. He throws himself at Jesus’ feet, praising God and giving thanks. And Jesus says to him, “Your faith has made you well.”

That last word in Greek—sozo—means much more than just “made well,” though. It means saved. It’s the same word used for salvation, for being rescued from death into life. Jesus addresses that same phrase to the woman who anointed his feet, the hemorrhaging woman, and the blind beggar at Jericho.

This Samaritan who returned to give thanks wasn’t only healed skin-deep, his demonstration of faith changed everything—and because of this, his healing wasn’t only physical, but came with the promise of salvation as well. All ten lepers were healed. But only one was made whole.

This story in Luke makes clear for us that there’s a danger in living only skin-deep lives, and that finally feeling comfortable in our own skin says nothing of the state our hearts and our souls.

Nine lepers were healed on the outside, but only one allowed gratitude to reach his heart. Nine were content with the gift; one turned back to thank the Giver. Nine walked away with clean skin ready to return to their old lives; one prostrated himself at Jesus’ feet and found new life.

And that’s the difference between being healed and being saved. Between fixing our outer selves and being made whole. Faith that only goes skin-deep is easily satisfied with blessings and rarely turns back to the One who blesses. Gratitude is what draws us deeper, what opens our hearts to resurrection life.

The Samaritan’s thanksgiving is his resurrection moment. He comes back to Jesus not because he wants more, but because he knows what he’s already been given. He recognizes the source of that gift. He knows that this healing isn’t just about his body—it’s about his whole self being restored to communion, to belonging, to God.

And in that moment, Jesus gives him more than just healing—Jesus gives him Himself. That’s resurrection life. That’s what it looks like when grace reaches beneath the surface and remakes us from the inside out.

The early Church Fathers used to say that thanksgiving is the language of the new creation. It’s the language of resurrection. Every time we give thanks—every time we turn back to God and say, “This life, this breath, this love, this forgiveness—all of it is gift”—we’re living as that one Samaritan leper lived. We’re stepping into the resurrection life that Jesus offers.

That’s why our central act of worship is called Eucharist, which literally means thanksgiving.

It’s the moment when we, too, turn back, fall at the feet of Jesus, and say, “Thank you.” It’s here that he not only heals us, but makes us whole. Not just cleanses us, but makes us alive again.

So this morning I’d like to leave us all with a couple of questions: Have we settled for skin-deep faith? Or for surface-level healing? Sometimes the feeling of being in our own skin is so uncomfortable that it’s hard to think about anything else. We want to belong, to be accepted by those around us, to be comfortable.

But the invitation we receive at every worship service provides us with a chance to change that…to be like the Samaritan, to return, to give thanks, and to find a deeper wholeness—to find resurrection life—in Jesus himself.

May we be followers of Jesus who live more than skin-deep lives—disciples who know the difference between looking healed and being made whole. And may our thanksgiving draw us ever deeper into the life of the risen Christ, who makes all things new.

Amen.